The Alevi faith, principles, beliefs, rituals and practices

The Alevi faith, principles, beliefs, rituals and practices

By Anatolia Report

August 2022

What is Alevism?

Alevism is not a stagnate belief but has evolved by interacting with various beliefs, spiritual doctrines and cultures over a wide geographical area from Central Asia to Balkan Mountains throughout the history. A process of gradual convergence between various different mystical schools since the 13th century constitutes what we call Alevism today. The concept of Alevi is actually a broad term covers different language and ethnic communities sharing same belief components. What defines Alevi belief can briefly be summarized as follows;

- In Alevism, every human being is a carrier of the essence from God.

- God in Alevism is Hakk, which means the truth.

- If God created all living thing then, human being is the most sacred thing in the world.

- Therefore, Alevis consider every living creature sacred as the carrier of an essence from God.

- Alevis call each other can (soul), which is gender-neutral name. As a result of this understanding, the position of women in Alevism is equal to that of men.

- Alevis consider god, cosmos and human in a total unity. This unity is symbolized with an exclamation, Hakk Muhammad Ali, which unities three most sacred person in Alevism, God, the Prophet Muhammed and Ali, cousin and son-in-law of the Prophet.

- A well-known verse of Hallacı Mansur, a Sufi poet from the 10th century, indicates the unit of God and human in Alevism, Ene’l Hakk (I am one with God).

- The founder saint of Bektashism, Haji Bektash Veli, from the 13th century explains this importance with his saying “My Kaabe is the human being”.

- Alevis do not consider God as fixed into a place of worship, iconography or written books but He is la-mekan (placeless) and human hearth is His only domicile.

- Therefore, Alevis do not fear God but only bear love for him and they do not believe in paradise or hell but an infinite circulation until one reach the status of perfection and reunion with where he or she comes form.

- Alevis consider all holy books and the prophets with great respect. Because, for them, the aim is one but ways to reach this aim can be various.

- This understanding prioritizes reason over dogma, as Haji Bektashi Veli says, “the end of the path would be dark if the path is not science.”

- Alevis consider all nations as one regardless of ethnic, racial, gender and linguistic differences simply because each creature carries the same sacred essence.

- Humanism, egalitarianism, mutual assistance, and gender-equality are the main social characteristics commonly shared by Alevi communities. Their lodge-centered social organization is based on a kind of agrarian socialism.

- A well-known sayings of Seyh Bedrettin, a religious scholar and rebel to the Ottoman Empire, “everything except the cheek of lover can be shared”, explains this egalitarianism perfectly.

- As a result, resisting against the injustice expressed with a phrase “allegiance with the oppressed (mazlum)” and “standing against the tyrant (zalim)” has become the main social attitudes in Alevism.

An Alevi is a person who follows faith of Alevism. As mentioned, the concept of Alevism is a broad concept covers various ethno-cultural communities has their own communal names such as Alevi, Bektashi, Kızılbaş, Tahtacı, Nusayri and Abdal are labeled in general with the concept of “Alevi”. It is not possible to locate Alevism in either Shi’ism or Sunnism as the two main branches of Islam. Today, we are very well informed about branches but not very confidents about roots of Alevism. The question of origin is still a controversial issue even among Alevis. Ali, as the main sacred person in Alevism, considers whole world as the place of worship, consequently, any good behavior can be classified as worship in this world.

Alevism have been forced for political reasons to live a closed social life in rural areas for centuries and as a natural result of this condition, they fundamentally dwell on the traditions of oral accounts and their unique social institutions. The oral tradition narrates the Alevi history embedded in epic tales as its nature would suggest. The oral tradition in Alevis takes its position among the public with saying which are performed together with the saz (a traditional music instrument) and lyric togetherness and menkıbes (mythical stories). Both of these elements contain to a great extent special sayings and meanings originating from the inner structure of the community.

Alevi Cosmology:

Alevi cosmology understands the relation between god, cosmos and human in a unity. Hallacı Mansur explains this philosophy as follows,

“There is no other being in the universe than God (unity of being). This states that; I am something, when trying to express oneself as something apart from God and that is wrong; therefore one has to only say I am one with God (Ene’l Hakk).”

It is believed that Haji Bektas Veli determines the principles necessary to become a mature human. He explains it by the statement “the servant is able to reach God through four gateways, forty stations and become his friends.” This gnostic understanding of self-spiritual-development is the main task before Alevis in their relation with the cosmos. Within this gradual development, human, as a being coming from the essence of the God, can manifest their sacred potential and evolve from the stage of ham (immature) into that of insan-ı kamil (mature). The stages of this process are explained as ; şeriat (sharia) is the way to be born, tarikat (is the way to promise), marifet is the way to be self-conscious, and hakikat is the way to find God in one’s own self. These stages are explained in analogy with educational system, from primary to higher education.

Jonh Kingsley Bridge briefly explains the doctrine of the four gateways in reference to Bektashism,

“the Şeriat:, (sheriat), orthodox, Sunni religious law, the tarikat or teachings and practice of the secret religious order, the marifet: mystic knowledge of God the hakikat: immediate experience of the essence of reality. A mystic teacher of Islam, one who sought as my mürşit [the spiritual guide] to teach me, explained to me the meanings of these four terms by taking the idea of “sugar” as an example. One can go to the dictionary to find out what sugar is and how it is used. That is the şeriat Gateway to the knowledge. One feels the inadequately of that when one is introduced directly to the practical seeing and handling of sugar. That represents the tarikat Gateway to knowledge. To actually taste sugar and to have it enter into oneself is to go one step deeper into an appreciation of its nature, and that is what is meant by marifet. If one could go still further and become one with sugar so that he could say, “I am sugar,” that and that alone would be to know what sugar is, and that is what is involved in the hakikat Gateway” Bridge (1937: 102).

Code of Morality in Alevism:

In Alevism, morality is the prerequisite of belief. A person, who is not capable of conserving his or her morality, is not regarded as suitable to participate in Alevi rituals. This morality is simply explained with the motto, “Being the master of one’s hand, tongue, and loins,” which requires Alevis not to behave immorally by using their hand (do not steal), their tongue (do not blasphemy), their loins (do not commit adultery).[1] These rules summarize a strong moral system, which is defined as “thinner than hair, sharper than sword.” Those who do not observe these basic moral principles are regarded as düşkün (the sinner), which is excommunicated from the community life with a strong social isolation.

Rites and Ceremonies:

It is a universal fact that all communities have their own faith practices and calendars originated from their particular cosmology.

Ayn-i Cem (the ritual of gathering) is the main ritual in Alevism. This special ritual is modeled on a mystical event, the Assembly of the Forty Being (Kırklar Cemi), includes 17 women and 23 men. They gather with the motto of “all for one, one for all.” This narrative portrays a sacred and secret gathering which the Prophet Muhammad participated on his way back from Miraç (heavenly journey in which he meets God). Ali, as the leader of this gathering, opens the secrets of belief to Prophet during the ceremony. The notable narrative used by Muhammed was “I am the city of knowledge but Ali is the gate.”

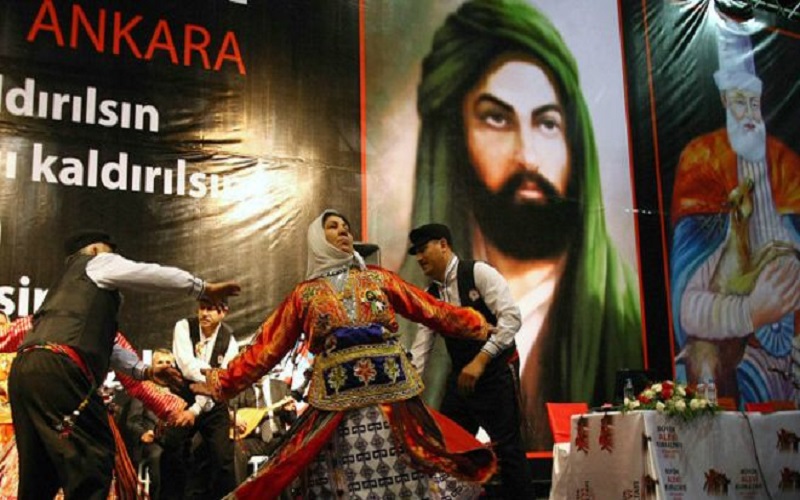

However, there are various forms of Cem. The most regular cems are conducted on weekly basis. In these gatherings where men and women can come together under the same roof, the belief community converse about daily as well as spiritual issues, chant Alevi deyiş (hymns), perform semah (ritual dance) and consume lokma (communal meal) at the end of the ritual. Given the fact that the human being is the most sacred thing in cosmos in Alevism, occasional muhabbet (conversation) is also frequently referred as a part of ritual. However, the significant gravity of the main cem rituals called ikrar (the admission) and görgü cemi (the manners ritual) cannot be denied in practicing Alevism.

Anyone who is born into an Alevi milieu is not directly accepted as an Alevi but has to be upgraded from the sphere of social to that of belief community. This upgrading is achieved with a special cem ritual, the admission, organized for a specific person who is willing to be upgraded. The requirement for admission varies in nuances according to different local traditions but a common framework requires the person to complete his or her adolescence, to be married, and to have musahip (eternal brother of the path). Once the admission is completed, the person has to observe certain moral principles and social codes briefly explained above. In this sense, görgü cemi (the manners ritual) appears as a communal mechanism to evaluate each member of the community whether they observe these principles and codes or not. These rituals are conducted in every year during the winter seasons. Each participant is asked to declare if he or she has any complains about any other members of the community. The community collectively judges those who are believed to violate any of moral principles and can be punished for their transgression by according to varying sanctions such as organizing a communal meal or paying for a communal project. If he or she violates one of the main taboos such as adultery or murder, the punishment will be capital and he or she is excommunicated from every sphere of communal life. This system of communal control is celebrated by Alevis as a perfect form of human sociality.

The Institution of Consent:

At the beginning of any ritual or ceremony, each participant is asked for his or her consent (rızalık) for the gathering. If he or she has any complaints, the community has to take this appeal into consideration. In principle, none of these gatherings can be initiated without the common consent of the participants. Alevism consider this mechanism as the genuine form of democracy.

The Institution of Spiritual Leadership:

Dedes (grand-father) are the group of spiritual leaders believed to be descended from the holy lineage coming from Ali, Ahl-i Bayt. Dedes are at the top of not only spiritual but also social role. They do not only conduct spiritual rituals but also guide all manners of social life. In principle, each Alevi community has to be subjected to a specific dede family. Each dede has also to be affiliated with a spiritual center called Ocak (hearth). There are also well-structural hierarchical relations among dedes as well as ocaks which are explained the principle El ele el Hakk’a (hand by hand, hand to God). In this sense, there is no omnipotent spiritual position in Alevism but a chain of auto-control. Each dedes is the guide of his talips (followers) but they are also subjected to the supervision of ocak as well as bounded by communal consent of their followers. There is a circular supervision among talips, dedes, and pirs, which is explained as el ele el hakka (hand by hand hand to God).

The Component of Alevi Belief Culture:

Music in Alevism:

Music is the most significant component of Alevi cultural life. Its presence is felt everywhere. Anatolian folk music is mostly based on Alevis. The greatest minstrels of Turkey have emerged from the Alevi community. Music is one part of Alevi rituals. Dede or Zakir supplicates (niyaz) to saz three times before cem, and then starts playing. Saz is also called “the stringed holy book.” As they say, there is no word without the saz, and no saz without the words. Saz (bağlama) is a holy musical instrument for Alevis. The feelings, thought and beliefs of the folk are expressed with the accompaniment of music. Deyiş, düvaz-imam, mersiye, miraçlama, semah are different types of Alevi Music.

Tradition of Aşık (Minstrel):

Aşık, Zakir or Ozan are terms used for the minstrel or bards who sing poems on belief and social issues, while playing an instrument. Minstrel also has significant position in Alevi worship. They acquire a holy personality by this position. Their music expresses also feelings and troubles of the Alevi folk.

Semah in Alevism:

Semah is a state of trace, constructed over the togetherness of Alevi music, teachings and dance. This state is regarded as part of worship, and is a distinctive feature of Alevism. It is an indispensable part of basic rituals of Alevi cem ceremonies. When it comes to the semah part of cem, Alevis perform ritual dance accompanied by the poetry sang and music played on saz. One of the most popular semah is Turnalar Semahı (the Crane Semah) which symbolizes the movements of crane, around a circle that symbolizes the universe.

Virtuous Personalities in Alevism: Poets and Saints:

Given the fact that poetry and music have indispensable significance in Alevi culture and spirituality, most of the virtuous personalities in Alevism are poets. In fact, Alevis specifically venerate seven poets as their grand poets who are Seyyid Nesimi (14th century), Yemini (15th century), Pir Sultan Abdal, Virani, Kul Himmet, Hatayi and Fuzuli (16th century). Apart from these seven grand poets, certain sainted persons are further accepted as sacred in Alevism such as Haji Bektash Veli (13th century), Abdal Musa (14th century), Yunus Emre (13th century), Kaygusuz Abdal (15th century), and 12 imams (e.g. I.Huseyin 7th century).

The Twelve Imams:

The Twelve Imams are another common Alevi belief. Each Imam represents a different aspect of the Universe and are recognized as twelve services or oniki hizmet which are performed by members of the Alevi community.

Imam Huseyin;

(3rd imam of 12): why Alevis respect Huseyin is because the way he lived and stand against tyrant Yezid in Kerbela in 7th century.

When Hüseyin clashed with Yezid’s army, Huseyin and his followers were 72 people and Yezid’s army was 3000 solders.

Huseyin said:

… Don’t you see that the truth is not put into action and the false is not prohibited? The believer should desire to meet his Lord while he is right. Thus I do not see death but see happiness, and prefer this to living with enemies in sorrow.

Mansur Al-Hallaj;

a Persian mystic poet. His politically critical and theologically heretic poetry, his exclamation in a state of ecstasy Ene’l-Haq (I am one with God, who is the truth) has become the motto explaining the relation between cosmos, God and human in Alevism.

However, he was tortured to death in 922 in Bagdad because his thoughts considered as blasphemous against Islam.

Haji Bektash Veli;

(master of Bektashi Dergahi, Academy), is the founder saint of Bektashism, Sufi spiritual order, established in the 13th century. His spiritual doctrine is accepted as one of the earliest form of universal humanism symbolized with the unity of a gazelle with a lion.

The heatless is from the flame, not from the iron sheet,

The miracle is in the head, not in the crown,

Whatever you are searching for, search in yourself,

Not in Jerusalem, or not in Mecca!

H.Bektashi Veli

Yunus Emre;

(student of Haji Bektash Veli), one of the most impressive poets of the Anatolian Sufi tradition, is believed to have lived in the 13th century. His poetry exemplifies unconditional tolerance in Alevism:

If you break someone’s heart

This prayer you perform is no good

None of the seventy two nations of the world

Can wash the dirt off your hands and face

Seyyid Nesimi;

who was born in 1369 in Bagdad, is the great sufi poet. His poetry advocated the philosophy of vahdet-i vücud (unity of existence). His ideas were regarded as blasphemous by the ulema in Aleppo, and he was executed by being skinned in 1417.

Come, come nearer,

There is a way to make up for missed prayer and fast

But not of the time passed without you

Pious people called this wine of love as a sin

I fill my goblet myself and drink it myself, it doesn’t interest anyone

Sometimes I fly to sky and watch over the world,

Sometimes go down to ground and world watches me,

Sometimes I go to medrese and study in the name of Allah

Sometimes I go to tavern and have fun of wine, it doesn’t interest anyone

Some asked “is the Nesimi” happy with his darling?”

I am happy or not, she is mine, it doesn’t interest anyone.

Shah Ismail (Hatayi);

a descendant of Azeri Sufi saint Safi-ad-din Ardabili and the founder of the Safavid Empire. Among Alevis, he is known by his poetry with the penname, Hatayi. His poets are still recited in Alevi rituals as deyiş (hymn). He died in 1524.

Pir Sultan Abdal;

(the follover of Haji Bektash Veli ) was a legendary Alevi poet who is believed to live in the first half of the sixteenth century. His poetry was very critical of the Ottoman Empire. He was put on trial and required to denial his adherence of Shah (Shah Ismail, hence, Alevism) but he refused to obey and executed by hanging by Ottoman Empire authority in 1550.

Virani Baba;

It is believed that he lived in the 16th century. In his poems, he reflected the hidden interpretations of letters and numbers in an enthusiastic and fluent manner.

I am a town crier in a great city

I am the crier; Ali is the warden of the market

If I buy less or if I sell more, it is still a profit

I am the crier; Ali is the warden of the market

Edip Harabi;

was born in 1853 in Istanbul. He worked as a clerk until he passed away in 1917 in Istanbul. He was known as an important Bektashi follower. His poet, Vahdetname (the poet of sacred unity) perfectly portrays how Alevis see the relation between God and human.

Before Allah and the world came into being

We created it in an instant and announced it

Before God had any worthy habitation

We took him in and became his host.

He didn’t yet have a name

He didn’t yet have material form

He didn’t yet have an appearance

We gave him a form and made it just like a person.

We became one with Allah here

We entered the place of pre-eternity and became one

We conversed there about the secret of the hidden treasure

We gave him the sacred name Compassionate.

Devriye by Şiri

Before the world came into being in the hidden secret of non-existence

I was alone with Reality in his oneness

He created the world because then

I formed the picture of Him, I was the designer

I became folded in garments made of the elements

I made my appearance out of fire, earth and water

I came into the world with the best of men

I was of the same age even as Adam

I came as Seth from the loins of Adam

As the prophet Noah I entered the flood

Once I became Abraham in this world

I built the House of God, I carried stone

I appeared as Ishmael once, O Soul.

I became once Isaac, Jacob,Yusuf

I came as Job, I cried out for mercy

Worms ate my body, I was in bitter mourning

They coy me in two along with Zachariah

With John they scattered my blood on the ground

I came as David, There were many who followed me

Often I carried the seal of Solomon

The blessed rod I gave to Moses

I became guide to all the Saints

To Gabriel the Faithful I was the right hand companion

From the loins of my father came Ahmed the chosen

The two-edged sword made its arrival from among those who guide on the way

Before the world was, friend to the People of the House

I was, while a slave, a fellow sharer of the mystery with God

I mediated much within myself

Without beholding a miracle I came to believe

With the Prince of Heroes I rode on Düldül

I bound on the Zülfikar, I carried the sword

Martyrdom in Alevism:

Alevis understand their historical origin with the motto “allegiance with the oppressed (mazlum)” and “standing against the tyrant (zalim)”. They seal their destiny in allegiance with Ali. His right to claim the caliphate was overridden from the political powerful rivals. Then, his two sons, Hasan and Hussein, were killed in their search for justice. The murder of Hussein with his 72 followers in Kerbela in 680 has significant importance in defining Alevi’s we-group identity. Following his death, many people took side with Ali’s cause throughout the history and they were punished for their advocacy of Ali. The execution of these people perfectly articulated with the perception of eternal victim destiny in Alevism. What is common in these historical events, “they were killed by a superior state authority which was either de jure or de facto Sunni Islamic” (Reinhard Hess 2007: 282). Reinhard Hess further differentiates the notion of Martyrdom in Alevism and Sunnism. The “absence of violent details… or aggressive interpretation… oriented towards an outward enemy” (ibid. 276) differentiates the notion of Martyrdom in Alevism from that in Sunnism. He also underlines that this album of martyrdom in Alevism is open to further affiliations.

For instance, the Abolishment of Janissary Organization in 1826 is understood as insistent continuation of the Ottoman oppression against Alevism. The Janissaries are infantry unity formed in the 14th century as the household troops of the Sultanate. The Bektashi order was appointed as the patron lodge to this special military force. The Janissary system became politically corrupted during the recession period. As a part of modernization reforms, Mahmut the Second attempted to abolish this force in 1826 and the Bektashi lodges were also aggressively targeted during the massive military campaign against the Janissaries.

It is popularly claimed that Alevis welcomed and venerated the establishment of Republic in 1923. However, this is not true for all Alevi communities, especially, those, who contravened or did not give support to the Republic, targeted by the military campaigns in 1921 in Koçgiri and 1938 in Tunceli. The abolishment of the main Bektashi Lodge in 1925 in accordance to the secularism caused irreversible devastations in their spiritual and social organizations.

This articulation gains obvious political characteristic in the 1970s. Alevi communities were victimized by rightist-Islamist militancy in the Middle and South-Eastern Anatolia during the political polarization in the 1970s. For instance, 111 Alevis were killed in a civil war-like clash in Maras in 1978. Reinhard Hess indicates that these civil victims as well as Alevi leftist militants are “quoted in an Alevi source in a line of continuity with traditional Alevi martyr figures” (2007: 281).

On the second day of the Pir Sultan Abdal Cultural Festival, 2nd of July 1993 in Sivas, a crowd of thousands people began protesting against the festival after the Friday prayer. When they could surrounded the hotel where the festival participants were staying, the protest got out of the control and 37 person lost their lives in the fire set by the Islamist militant. Two of them were among the protestors and another two were from the hotel personnel. The rest of 33 persons, also includes a Dutch female anthropologist, took their place in the line of martyrdom continuity.

Two years later, in the evening of the 12th of March 1995, an anonymous car opened fire with machine guns to three Alevi café-houses in Gazi District, historically left wing and Alevi shantytown area in Istanbul. An elderly dede, Halil Kaya, and another Alevi person lost their lives. Following this attack, the local residents organized a protest and marched to the police station in the district. The police responded their protest aggressive and the protest evolved into civil upraising and spread to other Alevi shantytown districts under partial curfew. 19 people lost their lives in three days uprising.

Alevi Geography:

It is a historical fact that Alevi settlements are concentrated more in remote mountainous areas in contrast to Sunni communities generally settled in plain and flat regions and usually dominated town and city centers. This social and geographical isolation is an obvious result of the confrontations between Alevis and Sunnis and centuries old oppression applied by the latter over the former. Given the fact that this geographical concentration determines their ways of living, Alevis were traditionally either semi-nomadic herding or household based agriculture society before the 1960s. Considering their economically and socially disadvantageous position emerged as a result of this isolation, it would not be surprising to note that Alevis largely participated internal and external migration waves started in the 1950s. Today, traditionally rural background Alevi communities have largely been urbanized in Turkey and Europe.

Alevis in Europe:

It is largely claimed that Alevis are overrepresented among internal and external migration waves emerged in the 1950s. The bloody attacks targeted Alevis at the end of the 1970s in Çorum, Elbistan, Maraş, Malatya, Sivas and Yozgat, enforced their participation especially in international migration waves to Europe. Today, it is estimated that approximately a million Alevis are living in Europe. The European Alevi Confederation represents more than 250 Alevi Cultural Centers, which are organized under national federations in Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Germany, France, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, and Switzerland.